It took some time to determine where and how a European satellite went after it fell out of space and burned up in the atmosphere.

Although they weren’t quite sure when, scientists knew that the European Remote Sensing 2 satellite (ERS-2) would return to Earth.

The satellite made a “natural” re-entry because the European Space Agency (ESA), which had been monitoring it as its orbit started to deteriorate, was unable to manage it.

Most of the satellite is expected to have burned up as it raced through the atmosphere, but some debris may have survived the fiery journey.

The ‘re-entry window’ for the satellite has narrowed throughout the day, with the ESA giving a final time as 5.05pm GMT – and for a while we weren’t sure if ERS-2 had actually re-entered the atmosphere or not.

A spokesman said at about 6pm: ‘We have now reached the end of the final re-entry window. We have received no new observations of ERS-2.

‘This may mean that the satellite has already re-entered, but we are waiting for information from our partners before we can confirm.’

At 8pm GMT, three hours after the ‘re-entry window’ ended, the ESA confirmed that ERS-2 did in fact arrive back on earth at 5.17pm.

It landed over the North Pacific Ocean between Alaska and Hawaii – despite the ESA predicting it would land closer to the east coast of central Africa, thousands of miles away.

Any pieces of the satellite that did survive were expected to be spread out over an area hundreds of kilometres long and tens of kilometres wide – mostly over the ocean – and the risk of debris posing danger to anyone on the ground was very low.

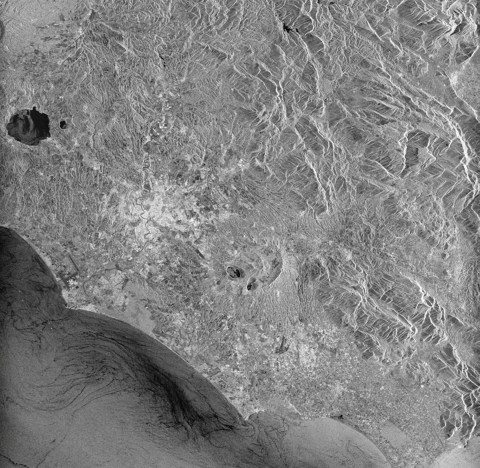

When it launched in April 1995, ERS-2 was the most sophisticated Earth observation spacecraft ever developed in Europe.

Together with the almost-identical ERS-1, it collected a wealth of valuable data on Earth’s land surfaces, oceans and polar caps, and was called upon to monitor natural disasters such as severe flooding or earthquakes in remote parts of the world.

In 2011, after almost 16 years of operations, ESA took the decision to bring the mission to an end. A series of deorbiting manoeuvres was carried out to lower the satellite’s average altitude and mitigate the risk of collision with other satellites or space debris.

‘The ERS-2 satellite, together with its predecessor ERS-1, changed our view of the world in which we live,’ said Mirko Albani, head of ESA’s Heritage Space Programme.

‘It provided us with new insights on our planet, the chemistry of our atmosphere, the behaviour of our oceans, and the effects of humankind’s activity on our environment.’